The Mortimer Country area has been described by the Council for the Protection of Rural England as one of the three most tranquil spots in the country.

Yet it wasn't always so....

In Roman times Leintwardine was an important garrison town.  The Roman frontier of Britain was marked by the Fosse Way, which ran from Isca (Exeter) to Lindum (Lincoln), via Corinium (Cirencester) and Ratae (Leicester). This frontier was secured by a series of Roman forts. The Roman frontier of Britain was marked by the Fosse Way, which ran from Isca (Exeter) to Lindum (Lincoln), via Corinium (Cirencester) and Ratae (Leicester). This frontier was secured by a series of Roman forts.

The Welsh Marches remained unconquered and the threat from these unconquered people unnerved the Romans. These fears, as well as the incentives of gold, silver, lead and copper drew the Romans towards the west and Herefordshire.

For a few decades of the middle of the 1st century AD the Welsh Marches formed the western Roman Frontier in Britain. Herefordshire in the centre of the Welsh Marches does have evidence of settlements created by the Romans in the border area.

Leintwardine, in the northwest of the county, shows signs today of its roots as a Roman fort. The high street, which runs straight through the centre of the village today, still represents the main street of a Roman settlement. The fort was built sometime after the 1st century AD and probably after the nearby fort at Buckton had been demolished. The purpose of the fort appears to have been that of a supply depot for the central Marches. It would have aided further forays into unconquered territory by the Romans and may have been held by a single unit of 500 men. Leintwardine, in the northwest of the county, shows signs today of its roots as a Roman fort. The high street, which runs straight through the centre of the village today, still represents the main street of a Roman settlement. The fort was built sometime after the 1st century AD and probably after the nearby fort at Buckton had been demolished. The purpose of the fort appears to have been that of a supply depot for the central Marches. It would have aided further forays into unconquered territory by the Romans and may have been held by a single unit of 500 men.

Closer to Hereford is the Roman town of Magnis at Kenchester, which lies just a few miles to the west of the City. Nothing survives of the town above ground but the perimeter of the town can still be traced in field boundaries, which enclose an area of 22 acres. Within the perimeter of the town were many substantial stone buildings and some even had mosaic floors, one example of which can be seen on the stairs of Hereford Library.

Other evidence of roman activity in Herefordshire takes the form of miscellaneous finds across the county and a legacy of Roman roads. Romans are famous for their very straight roads, which created the quickest route from A – B. Roman roads exist in Herefordshire at Eardisley, Craven Arms to Leintwardine which still goes by the name of ‘Watling Street’, and one running across the north of Hereford City, which today is still called the ‘Roman Road’. These roads were primarily designed to aid military communication and not communication between native settlements.

Later on the medieval Marcher Lords, after whom Mortimer Country is named, were ruthless power brokers, making and breaking alliances with kings, and even seizing the English throne for themselves following the Battle of Mortimer's Cross in 1461.

The Mortimer family arrived in England in the wake of William the Conqueror in 1066, and originally held land at and around Wigmore, near Ludlow. Their story is a colourful picture of ambition, power, rivalry and various attempts to claim the throne. Most of them were called Roger or Edmund, which adds to the colour and confusion of their tale

Here are some of the treacherous deeds the Mortimers instigated:-

Roger Mortimer (1287-1330) led the rebellion against the hopelessly inept Edward II. However, Mortimer went too far; he was instrumental in the barbaric murder of Edward II (after the king had been forced into abdication) and although he ruled as a 'regent' by default of his adulterous affair with Queen Isabella, his licence to rule by other nobles of the rebellion was soon overstretched and they had him arrested and put to death at Tyburn Hill. Roger's exploits were later made famous by the play 'Edward II', written in 1592, by Christopher Marlowe. He is portrayed at first as genuinely loyal to the concept of monarchy, but is debased by his own power and becomes a a callous and calculating traitor.

Edmund Mortimer (1391- 1425) - made a failed attempt to win the throne by proxy. He persuaded his cousin, Richard Earl of Cambridge (descendant of Edward II) to do the rebellious deed, but Richard failed and was put to death. Edmund - somehow - was spared...

Richard Plantagentet, Duke of York (1411-1460) made an attempt at the throne because his mother, Anne, was a Mortimer, and his father was the Earl of Cambridge from the last paragraph. He was the leader of the Yorkists in what became known later as the Wars of the Roses. Richard was involved in various battles - one at Ludford, near Ludlow, but was killed in battle at Wakefield. His son Edward then became leader of the Yorkists; he won a decisive victory at Mortimer's Cross and marched to London to successfully claim the throne

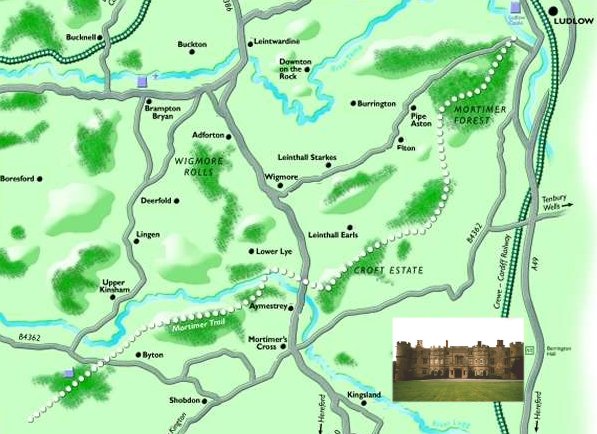

The Mortimer Trail is a new way-marked 30-mile trail, through the very heart of the ancient lands held by the Mortimer family, holders of the most powerful of the Norman earldoms. It passes through areas rich in natural history and human heritage, through the domain of deer and otter, kingfisher and heron, all overseen by buzzard and kite. Three rivers are touched on, the Teme, Lugg and Arrow valleys are secret gems along the way, ruined castles, medieval battle sites, Iron Age hill forts, glorious views, and dark woods. Interspersed are a series of traditional English villages, many of which still support self-sustaining communities.

The Trail follows the high ground, with fantastic views to the Black Mountains, Radnor Hills and Malvern’s. Delightful villages, rich history and abundant wildlife flourish in this peaceful area. The walking is moderate with several steep climbs; there are plenty of wooded areas to walk through, the area offers wonderful food, real ales and ciders and lovely atmospheric surroundings by night.

This map is reprinted with the kind permission of Mortimer Country Consortium : www.exploremortimercountry.co.uk

Starting in the Mortimer forest above Ludlow and its castle it progresses towards the Saxon town of Kington, meandering along lovely ridges and deep valleys with great views to the Cotswolds to the south, the Malvern’s and Clee Hills to the east, the Shropshire hills to the north and spectacular views into Mid Wales in the west. Starting in the Mortimer forest above Ludlow and its castle it progresses towards the Saxon town of Kington, meandering along lovely ridges and deep valleys with great views to the Cotswolds to the south, the Malvern’s and Clee Hills to the east, the Shropshire hills to the north and spectacular views into Mid Wales in the west.

From Ludlow to Aymestry 13 miles walk and from Aymestry to Kington a 17 mile walk

Ludlow, with its beautifully preserved black-and-white half-timbered buildings clustered beneath a huge castle, is one of the most picturesque towns in England. The castle was a stronghold of the Mortimer's, powerful Marcher Lords who were given vast estates along the Marches or Border Country of England and Wales by William the Conquer in return for guarding the frontier.

Ludlow Castle : Construction began in the late 11th Century as the border stronghold of one of the Marcher Lords, Roger De Lacy. Early in the 14th Century it was enlarged into a magnificent palace for Roger Mortimer, then the most powerful man in England. Later, in the 15th Century under the ownership of Richard, Duke of York, the Castle was involved in the Wars of the Roses before becoming a royal palace. In 1472 Edward IV sent the Prince of Wales and his brother (later the 'Princes in the Tower' of Shakespeare fame), to live at the Castle, which was also the seat of Government for Wales and the boarder Counties.

In 1501 Price Arthur, (son of Henry VII and brother to Henry VIII) with his bride Catherine of Aragon, lived here for a short time before his early death. Queen Mary Tudor and her court spent three winters at Ludlow between 1525 and 1528. In 1689 the Royal Welsh Fusiliers were founded at the Castle by Lord Herbert of Chirbury but soon after it was abandoned and fell into decay. In 1811 the 2nd Earl of Powis, in the ownership of whose family it remains, purchased the ruins from the crown.

The Castle's long history is reflected in its varied architecture; Norman, Medieval and Tudor, many of the buildings still stand. From the huge Outer Bailey a bridge across the moat leads to the Inner Bailey with the Keep, the Great Chamber, the other side of the moat is the Ice House - once used to store explosives. Milton's famous Comus was first performed in the Great Hall in 1634 and the tradition of a performance is continued each June and July when a play is performed in the open air within the Inner Bailey, as part of the Ludlow Festival. The Castle hosts other events throughout the year. The Castle's long history is reflected in its varied architecture; Norman, Medieval and Tudor, many of the buildings still stand. From the huge Outer Bailey a bridge across the moat leads to the Inner Bailey with the Keep, the Great Chamber, the other side of the moat is the Ice House - once used to store explosives. Milton's famous Comus was first performed in the Great Hall in 1634 and the tradition of a performance is continued each June and July when a play is performed in the open air within the Inner Bailey, as part of the Ludlow Festival. The Castle hosts other events throughout the year.

The Mortimer family were stewards to large areas of border country around Ludlow, covering parts of South Shropshire, North Herefordshire and Powys.

The Medieval Mortimer Family : Mortimer is one of the easier surnames to account for. It is one of a handful of names, which became hereditary in the eleventh century. The first to be so called, Roger, was seigneur of the castle and township of Mortemer sur Eaulne, a place situated on a hill, which had at some point been surrounded by an ox- bow lake of the River Eaulne. This stagnant water (the name means 'dead sea' or 'dead pool') around the town gave the place - and the family - its name. It may romantic to think, as the Victorians did, that the name was brought to England by a returning crusader who had visited the shores of the Dead Sea, but the family is actually named after a large, smelly puddle in France.

In 1054 there was an important battle at Mortemer, known afterwards as the battle of Mortemer en Brai. Roger found himself fighting for his lord, Duke William of Normandy, against an army of Frenchmen. Duke William won. Unfortunately for Roger, he had previously sworn allegiance to one of the Duke's prisoners, the Count of Montdidier, who was entrusted to his custody. By feudal law and the oaths he had sworn Roger was bound to release him. When Duke William found out that Ralph de Montdidier had been set free he was justifiably angry. The lordship of Mortemer was confiscated and given to Roger's relation, Ralph de Warrenne.

Despite this early loss of their seat, the name of Mortimer stuck. Roger's heir Ralph came to England and took a conspicuous part with Roger de Montgomery in the defeat of Wild Edric of Shrewsbury at Wigmore Castle in 1074. As a result of his service he was rewarded with many of the manors of the late Earl of Hereford, who had also taken part in the rebellion. At the time of Domesday (1086) Ralph found himself lord not only of Wigmore Castle but also of many other manors stretching across twelve counties, with no fewer than nineteen manors in Shropshire alone. The basis of the medieval English dynasty had been laid.

A number of English noble families carried the name Mortimer and it is probable that they were all descended from Ralph. The lords of Attleborough in Norfolk and the lords of Richard's Castle in Herefordshire were two families, which were connected and probably descend from the Mortimers of Wigmore, although it cannot be proved. From the Mortimers of Richard's Castle sprang the barony of Mortimer of Zouche. At an early date Alan de Mortuo Mari (the Latin spelling of the name which normally occurs in medieval documents) took the bold step of adventuring into Scotland, marrying the heiress of the de Vipont family and thereby aquiring the castle of Aberdour. From the main branch of the family sprang Mortimer of Chirk and the Mortimer lords of Chelmarsh. Thus within a short time - two centuries - the family had bred and spread across the country like Norman rabbits.

Most famous of all the families to bear the name Mortimer was that of the heirs of Ralph. This was the Mortimer family of Wigmore, later Earls of March. They made their mark upon English history by marrying well, sometimes spectacularly well, fighting well, never failing in the male line (until 1425) and being prepared to exploit their position on the Welsh march to the full. By the end of the fourteenth century they had risen to be heirs to the throne and were among the richest families in England.

In Norman times they were relatively lowly lords, their manors securing for them a place in the third or perhaps lower second tier of the nobility. In the early twelfth century they conquered a large swathe of mid-Wales, Maelienydd, which they ruled as magnates thereafter. They regularly killed or blinded Welsh princes caught in battle and maintained the border by sheer force. Diplomacy was not beyond them, however, and a great success was acheived when one of the most warring Mortimers, Roger (d1215), settled the ownership of Maelienydd for good with Llywelyn the Great. This Roger's second son, Ralph, who inherited Wigmore on the death of his brother, pulled off an even bigger coup in marrying Llywelyn's daughter, Gladys the Dark. Being half Welsh did not stop the next heir, another Roger (1232-1282) from fighting his cousin Llywelyn ap Gruffydd, the last free prince of Wales, until Wales was a spent force. In 1282 it was Roger's four sons who tracked down Llywelyn, killed him and carried his head to London.

The Mortimers played their part in English politics as well as Welsh. They fought for William Rufus against Robert Curthose, resisted Henry II's rule in the mid twelfth century and supported King John vigorously in the early thirteenth. When Simon de Montfort took arms against the King, Roger Mortimer at first backed him but then changed sides. At the Battle of Lewes in 1260 Roger supported the King and consequently lost his five hundred men-at-arms in the ensuing rout. Roger himself barely got away that day. Afterwards he proved a loyal servant to King Henry, rescuing the heir to the throne (the future King Edward I) from captivity in Hereford Castle. Finally, at the battle of Evesham, Roger Mortimer took command of the vanguard. At the end of the battle, de Montfort's head was cut off and sent as a present to Lady Mortimer at Wigmore. Delightful.

The above-mentioned Roger Mortimer (1232-1282) raised the family to new heights in his wars against Llywelyn and de Montfort. Indeed, he was made Regent of England on one occasion and gathered many more estates to his credit. But the most remarkable of all the lords of Wigmore was yet to come. Roger's grandson, another Roger, inherited wide estates in England, Wales and Ireland, married well, became a successful soldier in Scotland, Wales, Ireland and France and staged a revolt against the king. He was betrayed, forced to surrender, sentenced to death, reprieved, and locked up in the Tower of London. Hearing of a plot to murder him in the Tower, he escaped over the walls, fled to France and there seduced (or was seduced by) the Queen of England, Isabella. Together they travelled to Holland and bartered the hand in marriage of the future King Edward III (then fourteen years old) for a small army. Then they returned to England, routed King Edward II and forced him to abdicate. Roger probably ordered the King's fake death to be announced in September 1327. Through his kinsman Thomas Berkeley and his old comrade-in-arms, Sir John Maltravers, he then kept the old King alive as a political prisoner for the next three years (for the scholarly argument underlying this, see 'The Death of Edward II in Berkeley Castle', English Historical Review, vol. 120, no. 489 (2005)). During this time he forced the young king to recognise the independence of Scotland, sacrifice his claim on the throne of France, executed the Earl of Kent (Edward II's brother) for trying to rescue the ex-King from Corfe Castle and demanded for himself the premier earldom in the country: becoming Earl of March in 1328. He also continued his illicit affair with Queen Isabella, and may have had an illegitimate child by her. He was finally arrested at Nottingham Castle by Edward III on 19 October 1330, and hanged 'like a common criminal' at Tyburn six weeks later. You can say many things about Roger Mortimer, 1st Earl of March, but one thing he was not was a common criminal.

You can say many things about Edward III too but one thing he was not was the bearer of a grudge. Although he confiscated all the Mortimer estates on the execution of the 1st Earl of March, he restored the last of them, as well as the earldom, in 1356 to the earl's grandson, another Roger. He even restored some of the lands, which the 1st Earl had stolen. The second Earl fought dutifully, being knighted alongside the Black Prince on the field at Crécy in 1346. Unfortunately he succumbed to a sudden illness while fighting at Rouvray in 1360. His son, Edmund, thus became the 3rd Earl. Edward III showed even greater favour to this descendant of his father's murderer by allowing him to marry his granddaughter Philippa, daughter of his second son Lionel. This brought the Mortimer family the further earldom of Ulster and Connaught. Moreover, after it transpired that the bloodline of the Black Prince would go no further than Richard II, it meant that the Mortimers were now the heirs to the throne.

Being the heir to the throne in the fourteenth century was dangerous. One was not just handed a poisoned a chalice, one was forced to drink from it regularly. After the 3rd Earl was killed in Ireland, his son took on the mantle of heir. He spent his life being hounded and living in closely guarded captivity. In the end he was killed in Ireland, just as his father had been, leaving his seven year-old son all his titles and the responsibility of succeeding to the throne. But Richard II was deposed the following year and Henry IV took power. There were many who wanted to see Henry IV replaced with young Edmund Mortimer, but Edmund knew which side his bread was buttered and told Henry of any strategy he discovered to make him king. Even his own uncle, another Edmund Mortimer, plotted to put the young 5th Earl of March on the throne. This Edmund was starved to death in Harlech Castle and his wife and daughters murdered. Such were the times.

Edmund himself never had any children. Although Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, for many years he resisted the obligation to go there, where his father and grandfather had died. He was right to be suspicious. In 1424 he was ordered to put down an Irish rebellion - and when his representative proved incapable of so doing, he was ordered there in person. Thus he too perished in Ireland. With him died the last of the male line of the Mortimers. His sister Anne, who had married the Earl of Cambridge, became heiress to all the estates of the Mortimer family and their titles. In turn these passed to her son, Richard, Duke of York. He took up arms against Henry VI and, with the help of the Earl of Warwick, led the Yorkist faction at the outbreak of the Wars of the Roses. After his death at the battle of Wakefield, his son carried on the fight against the Lancastrians, being victorious at the battle of Mortimer's Cross in 1461 (a mile or so from Wigmore Castle) and securing the crown for himself as Edward IV. Thus all the family estates and titles were subsumed in those of the new royal family.

|